Lydiard Park is listed as Grade II in Historic England’s register of the most important gardens and historic landscapes in England. Once the private pleasure grounds of the St. John family, its historic features can now be freely enjoyed by all who visit.

Originally a medieval deer park carved out from the forest of Braydon, Lydiard Park has evolved over the centuries. Today you can still discover many clues and distinctive architectural features which were investigated and restored in a £5.3million project in 2004-7. Check back soon for some of the highlights of the restoration.

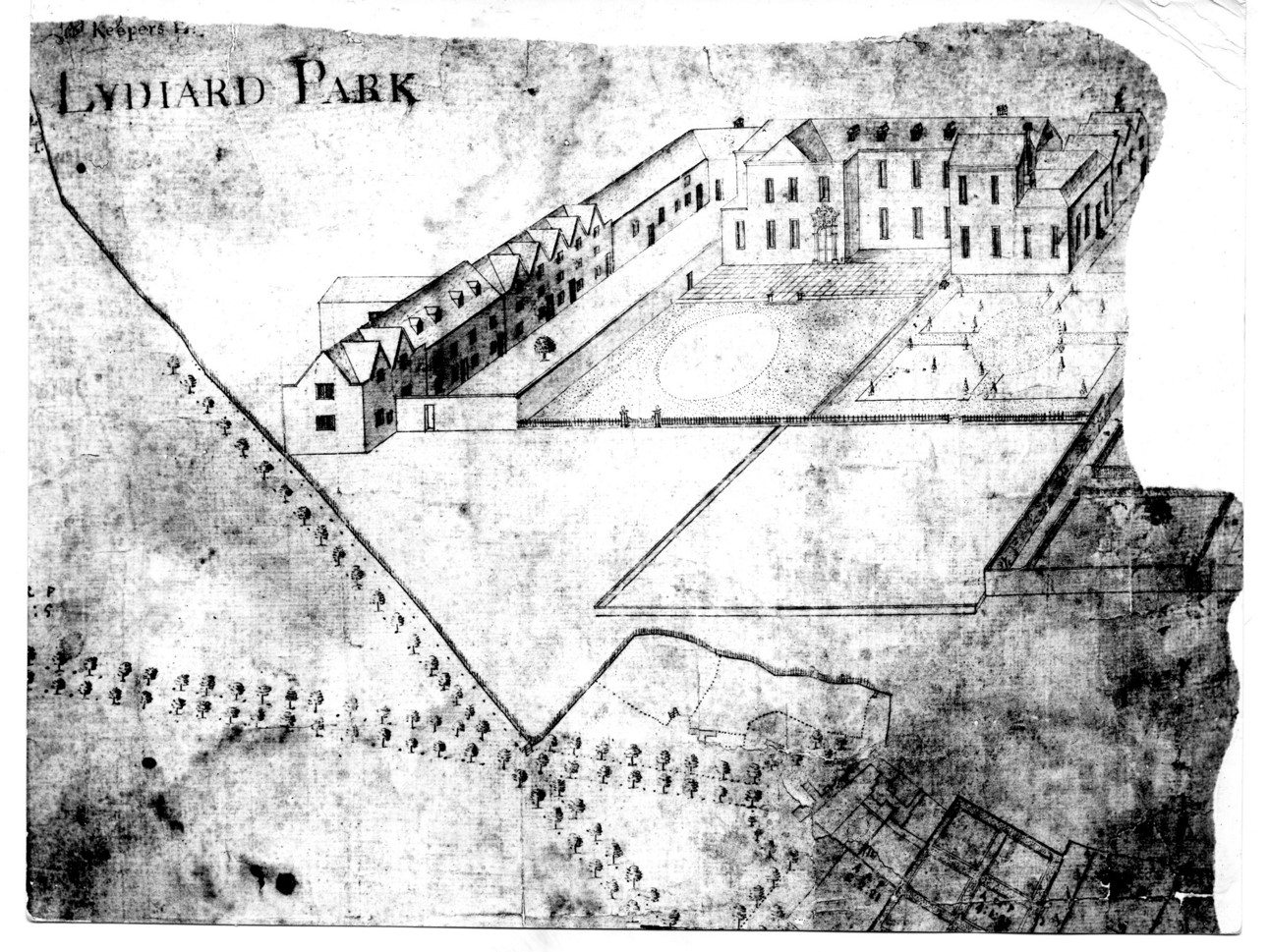

17th Century Formal Gardens, Lydiard Park c1700, Warwick County Record Office

17th Century Formal Gardens, Lydiard Park c1700, Warwick County Record Office  Johanna StJohn 1631-1705

Johanna StJohn 1631-1705 The first baronet, Sir John St. John (died 1648) is credited with creating formal gardens and remodelling the medieval house. Sir John made Lydiard Park his principal residence, and from 1615 he invested in in splendid monuments in the church including the Golden Cavalier, a memorial to one of the three sons lost in the Royalist cause during the Civil War.

The earliest known plan of the park was made in 1700. It shows a birds- eye view of the Elizabethan style manor house fronted by a gravel forecourt, railed and gated from the park.

Beyond the house to the south east, where the current lawn sweeps down to the lake, the plan shows a grid of formal gardens with topiary, paths and terraces overlooking a formal canal. Straight lined avenues stretch out towards the wider estate. The discovery of a bowling ball during excavations in the lake shows that the gardens were also used for bowling in the 17th century.

Sir John’s daughter in law Lady Johanna St John was the real garden enthusiast and the new plantings and brickwork shown in the 1700 plan point to her influence. She had an extensive knowledge of plants and herbs and their healing properties and kept a record of the poultices, purges and potions she made. Humps and bumps are still visible on the lawn today, clues to the lost gardens of Lydiard.

Beyond the canal the Old Pond was a remnant of the medieval deer park, used for the production of tench, carp and other fish. Fish were used to feed the family during Lent and on Fridays, but the pond also served as a ready-made larder for visitors.

In 1738 Henry St. John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke renounced his interest in Lydiard in favour of his half- brother John or ‘Jack’, tasking him with putting the seemingly neglected old house into better order. Armed with his wife’s fortune, Jack set about remodelling the house in the fashionable Neo Palladian house we recognise today.

Jack complemented the revamped house with a radical restyling of the gardens in what has become known as the ‘English Landscape Garden Style’ made famous by William Kent and Capability Brown. This naturalistic style landscape has regularly been called Britain’s greatest contribution to European art.

Jack swept away Lydiard’s formal gardens to make way for a large lawn and re-used the bricks for a new walled garden to the north west of the house. Plants from the earlier garden would also have been transplanted. Archaeology undertaken during the park restoration project revealed narrow flower beds, wide gravel paths and a fine stone water trough suggesting an enclosed formal flower garden. The garden was shaped in a parallelogram to take full advantage of the sun, and a sundial bearing the arms of Henry 1st Viscount St. John was set within it.

Dam wall - Copyright Jane Gifford 2007

Dam wall - Copyright Jane Gifford 2007  Lord Bolingbroke’s brood mare in the grounds of Lydiard Park, 1766

Lord Bolingbroke’s brood mare in the grounds of Lydiard Park, 1766  The ice house

The ice house A great castellated dam wall replaced a more modest structure, and the formal canal was given softened contours to make it appear a more natural looking lake – all part of the quintessentially English Landscape Garden Style which we are familiar with at Lydiard today.

Thanks to Jack’s successor, Frederick, 2nd Vsct.Bolingbroke, a painting of the newly remodelled house and park exists, albeit as a backdrop to the viscount’s favourite brood mare.

Frederick, a keen gambler and racehorse owner, was an early patron of the great equestrian painter George Stubbs. A copy of ‘Lord Bolingbroke’s Brood Mare in the grounds of Lydiard Park’ can be seen in the Library of Lydiard House.

An ice house was a highly desirable component of any grand 18th century park. Lydiard’s is largely buried and well–insulated. You can find it on the route between the Forest Café and the Coach House. It was built to store ice for one or two years, allowing the cooks to make chilled food and luxury deserts. Ice would have been collected from the frozen lakes in hard winters, carted to the ice house, and stored in layers with salt and straw.

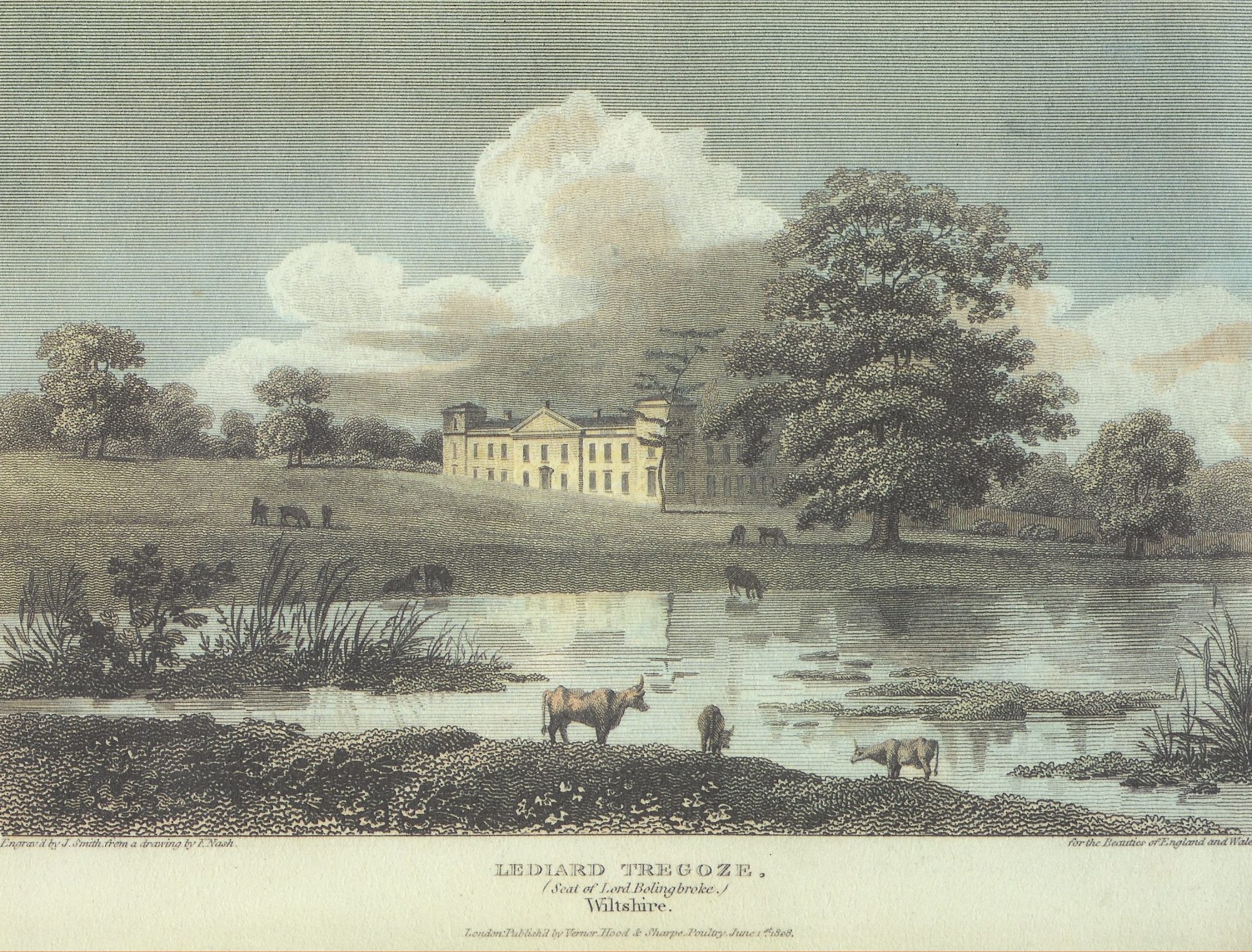

Lydiard Park by Nash, Britton's 'Beauties of England and Wales' (1808)

Lydiard Park by Nash, Britton's 'Beauties of England and Wales' (1808)  Photograph by Nevil Story Maskelyne

Photograph by Nevil Story Maskelyne At the beginning of the 19th century Lydiard Park was considered one of the beauties of England. This picturesque view by Nash shows open grassland with a few large oak trees and a young Cedar of Lebanon, now sadly fallen. Cedars of Lebanon, made popular by Lord Burlington at Chiswick House, graced many a stately home.

A more unusual feature to find, Lydiard’s Plunge Pool is believed to be a rare, surviving example of an open air cold bath. Immersing yourself in cold water was considered to bring health benefits and one wonders who used the pool at Lydiard; perhaps it was the aging 3rd Viscount or one of his aristocratic tenants.

No great changes happened to the park in the 19th century except for a new drive leading to the house and church from the north and a new service wing. Possibly a sign of declining fortunes, the lawn stretching between the house and the lake was given over to hay making as shown in a very early photograph by Nevil Story Maskelyne.

Throughout this century the park was used for shooting. Game records show hares, pheasants and rabbits were regularly shot in large numbers, though the deer park was no longer kept up.

Rear of Lydiard House in dilapidated state

Rear of Lydiard House in dilapidated state  Huntingdon Elms

Huntingdon Elms In 1911 the great dam collapsed, leaving only boggy pools where the lower lake had been. The same year, Huntington Elms were planted along the north drive though they succumbed to Dutch Elm disease in 1976 and were later replaced by the present lime avenue.

By the 1930’s, in increasing financial difficulties, the family had sold the greater part of their ancestral estate at Lydiard. In 1941 Lydiard Park was requisitioned and the 6th Viscount left the mansion which was not occupied as it was deemed ‘unfit for habitation’.

Finally, in 1943, 750 acres were sold, with the house and the remaining 147 acres going to Swindon Corporation. Lydiard was saved from likely post-war demolition and development and the once private estate became a people’s park.