When John met Lucy it wasn’t her shy smile or her slender ankle that won his heart. John Hutchinson, a 22 year old law student at Lincoln’s Inn, fell in love with Lucy Apsley after browsing through her Latin notebooks.

Lucy Apsley was the granddaughter of Sir John St John and his wife Lucy Hungerford. Sober and scholarly, Lucy has left a wealth of writing – essays, poetry and her invaluable account of a family at war in The Life of Colonel Hutchinson.

Lucy was born on January 29, 1619/20, the fourth child and eldest daughter of Sir Allen Apsley and his third wife, the former Lucy St. John.

Lucy records that she was born at ‘about 4 of the clock in the morning’ in the Tower of London where her father was Lieutenant.

She writes how after three sons her mother was ‘very desireous of a daughter.’ While pregnant Lady Apsley had a dream that she was walking in the garden with her husband when a star fell from the sky into her hand. Sir Allen interpreted the dream to mean that they would have a daughter of extraordinary distinction.

However, the nurses in attendance at her birth expressed concern at the baby’s heightened colour and feared she would not live, according to Lucy.

It’s fair to say that Lucy was the apple of her parent’s eye. Quick to count her many blessings, Lucy acknowledged the advantageous circumstance of her birth and in particular the education her parents provided for her. She recalled learning to speak in both English and French and how by the age of four she was reading ‘perfectly.’

As a seven year old the young Lucy had no less than eight tutors to school her in languages, dancing, writing and needlework (which she hated). In fact, she spent so much time studying that her mother feared for her daughter’s health and locked away her books.

“After dinner and supper I still had an hower allow’d me to play, and then I would steale into some hole or other to read,” Lucy writes.

She describes how she enjoyed the company of adults in preference to her same age playmates. ‘Play among other children I despis’d, and when I was forc’d to entertaine such as came to visitt me, I tir’d them with more grave instructions than their mothers, and pluckt all their babies [dolls] to pieces.’

John was lodging at the home of his music teacher Mr Coleman when he met fellow student Barbara Apsley, Lucy’s younger sister. Barbara talked at length about her sister Lucy and showed John some of her poetry.

While John Hutchinson was leafing through Lucy’s Latin books, Lucy and her mother were visiting relatives in Wiltshire where a marriage settlement was under discussion.

Fortunately for the smitten young law student the negotiations had come to nothing and the young couple met for the first time at a party at Syon House, the home of the Duke of Northumberland.

John’s affections were reciprocated and Lucy, who paid little heed to fashion and outward appearances, allowed herself a little leeway when it came to describing her suitor.

‘She was surpriz’d with some unusuall liking in her soule when she saw this gentleman, who had haire, eies, shape, and countenance enough to begett love in any one at the first, and these sett off with a gracefull and generous mine [mien] which promis’d an extraordinary person.’

But mischief makers tried to drive them apart. John’s friends advised him to be cautious while ‘the weomen, with wittie spite, represented all her faults to him, which chiefely terminated in the negligence of her dresse and habitt and all womanish ornaments, giving herselfe wholly up to studie and writing,’ Lucy recorded.

But of course this is exactly what John loved about her.

With the critics silenced and the wedding date set, disaster struck. On the very day the couple were to exchange their vows Lucy fell ill with small pox. For several days her life hung in the balance. According to Lucy’s account the disease made her ‘the most deformed person that could be seene for a greate while after she recover’d. Yett he was nothing troubled at it, but married her assoone as she was able to quitt the chamber, when the priest and all that saw her were affrighted to looke on her.’

The couple were eventually married on Tuesday July 3, 1638 at St Andrew’s Church, Holborn and began married life with Lucy’s mother at Bartlett’s Court. Lucy quickly fell pregnant but miscarried twins and nearly died herself. Quickly pregnant again, her health gave cause for concern and her worried mother and husband moved her out of London to a property called Blew House in Enfield Chace where Lucy gave birth to twin sons, Thomas and Edward.

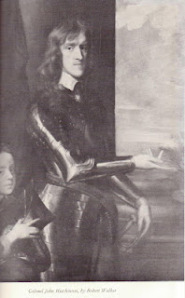

The couple’s continuing love affair would be played out against the backdrop of civil war in which Lucy’s Parliamentarian husband played a prominent part. John was Governor of Nottingham Castle 1643-47 and in 1649 was one of the judges at the trial of Charles I. His signature appears on the King’s death warrant.

In 1663 John was arrested on suspicion of being involved in the Northern Plot and was imprisoned in the Tower. The following year he was transferred to Sandown Castle in Kent where he died four months later.

Lucy’s account of her husband’s life has been criticised for her exaggerations of his virtues. She would continue to protest his courage and his innocence. The inscription she had carved on his memorial at St Margaret’s Church, Owthorpe reads:

‘He died at Sandowne Castle in Kent, after 11 months harsh and strict imprisonment, – without crime or accusation, – upon the 11th day of Sept 1664, in the 49th yeare of his age, full of joy, in assured hope of a glorious resurrection.’

It is believed that Lucy began her account of her husband’s life for her children soon after his death.

Their love affair transcended death as Lucy wrote:

‘Soe, as his shaddow, she waited on him every where, till he was taken into that region of light which admitts of none, and then she vanisht into nothing.’

To be continued…